Notes on Environmental Economics, Externalities, Tragedy of the Commons, etc. (ECON 262)

Economists tend to approach environmental issues the same way they approach all social issues. The same assumption (self-interest) about human behavior is made and the analysis follows from that assumption.

So remember Rules – Incentives – Actions – Outcomes!!!!

Economists also tend to emphasize cooperative solutions over one's that entail conflict and coercion. Conflict usually comes about via politics. Look at the conflict that takes place in Washington, D.C. every day.

ALWAYS REMEMBER - perfection is unattainable (whatever that may be). We can't judge any policy, law, institution, economic system, etc. against perfection - we must judge it against a viable alternative!!

And keep these principles in mind:

1. Always think about costs. For example, is the optimum level of “pollution” zero? Think about it.

2. Incentives matter!! If you set up the rules such that people don't agree with them (they go against their interests) - it is guaranteed that there will be unintended (almost always negative) outcomes - often the opposite of what was intended.

Let's first look at:

Economic Growth and the Environment - Are They Compatible?

One Theory: As people's incomes increase with private property rights, economic freedom and trade, their willingness to pay for protecting the environment increases.

In other words, environmental quality is a normal good.

Environmental Kuznets Curve

Some economists have found that pollution often appears first to worsen and later to improve as countries’ incomes grow.

Because of its resemblance to the pattern of inequality and income described by Simon Kuznets, this pattern of pollution and per capita income has been labeled an ‘environmental Kuznets curve’.

The theory: at relatively low levels of income the use of natural resources and/or the emission of wastes increase with income. Beyond some turning point, the use of the natural resources and/or the emission of wastes decline with income.

GRAPH:

Why? Reasons for this inverted U-shaped relationship are hypothesized to include income-driven changes in:

(1) the composition of production and/or consumption - people can afford to change both how they produce goods/services and they can afford to choose goods/services that are more compatible with a better environment.

(2) the preference for environmental quality - environmental quality is seen as a "normal good." People demand more of it as their income increases.

(3) institutions that are needed to internalize externalities - these become "affordable" at higher incomes. Could be government institutions or private institutions - with high transactions costs in trade (the fly fishing example), people can afford to pay them with higher incomes.

(4) increasing returns to scale associated with pollution abatement - with higher incomes, more people demand environmentally friendly goods - so firms are able to produce them cheaper due to increasing returns to scale (economies of scale).

The Evidence

It is mixed - and depends upon the "type" of environmental problem studied.

But first - What is the relationship between economic freedom and environmental health? Here is what one study found:

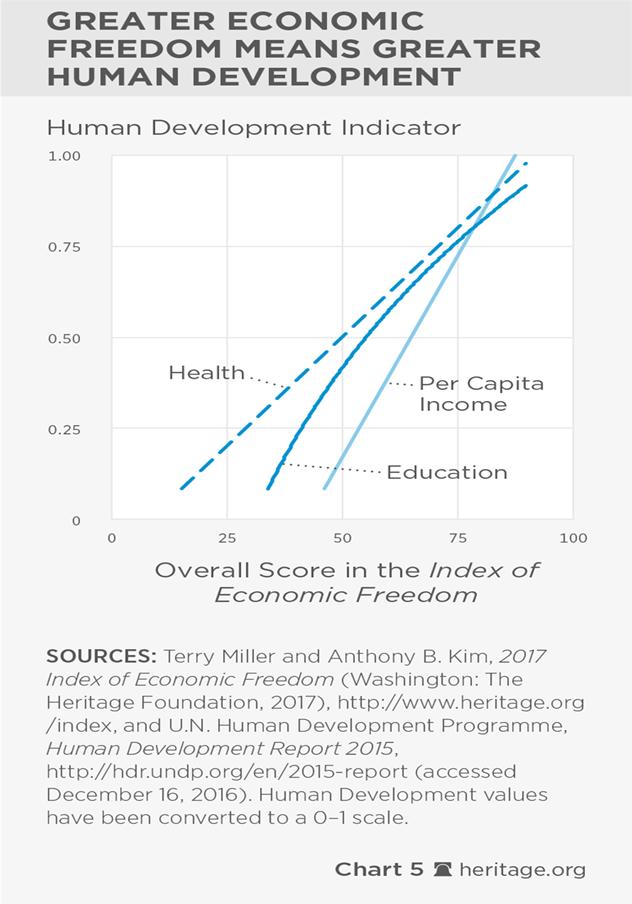

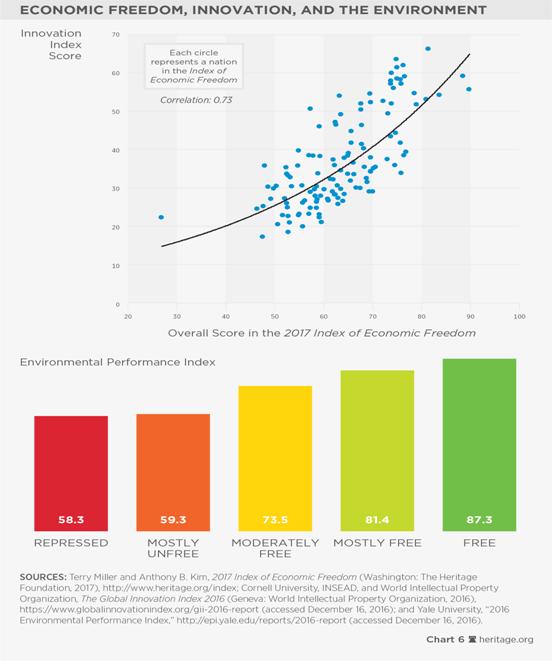

From: Report on the 2017 Index of Economic Freedom

By Terry Miller and Anthony B. Kim

They found that Economic Freedom Facilitates Innovation and Better Environmental Protection

The positive link between economic freedom and higher levels of innovation ensures greater economic dynamism in coping with various developmental challenges by spurring a virtuous cycle of investment, innovation (including in greener technologies), and dynamic entrepreneurial growth.

In addition, the fact that the most remarkable improvements in clean energy use and energy efficiency over the past decades have occurred not as a result of government regulation, but rather as a result of advances in technology and trade should not be overlooked. Around the world, economic freedom has been a key factor in enhancing countries’ capacity for innovation and, by so doing, in improving their overall environmental performance.

However,

some economists found that while many pollutants exhibit this pattern, peak pollution levels occur at different income levels for different pollutants, countries and time periods.

Most famous studies are from those that really introduced the idea - Grossman and Krueger (1995) used a simple empirical approach. They looked to see if there is a correlation in the data between air and water quality in cities worldwide and income per capita and other city and country characteristics. They found that many of the plots of data appear inverse-U-shaped, first rising and then falling. The peaks of these predicted pollution-income paths vary across pollutants, but in most cases they come before a country reaches a per capita income of $8,000 in 1985 dollars (Grossman and Kruger, 1995, p. 353).

Note: $8,000 in 1985 would be about $18,299.27 now.

Many other studies have followed. Some generalizations across these studies have emerged.

a. Roughly speaking, pollution involving local externalities begins improving at the lowest income levels. Fecal coli form in water and indoor household air pollution are examples. For some of these local externalities, pollution appears to decrease steadily with economic growth, and we observe no turning point at all. This is not a rejection of the EKC; pollution must have increased at some point in order to decline with income eventually, and there simply are no data from the earlier period.

b. By contrast, pollutants involving very dispersed externalities tend to have their turning points at the highest incomes, or even no turning points at all, as pollution appears to increase steadily with income. Carbon emissions provide one such example. This, too, is not necessarily a rejection of the EKC; the turning points for these pollutants may come at levels of income per capita higher than in today’s wealthiest economies.

These could both be predicted theoretically. The closer one is to the cost of his own actions, the more likely he will do something about that cost. Living with open sewer at your front door - well, brings action sooner. Driving a car and not recognizing the externality at the moment - action is put off.

Criticisms of the Theory:

1. Methods used in the studies have been criticized. Measuring the pollution, for example. And other statistical problems.

2. More developed countries could be shipping their pollution to the less developed countries - this skews the results. Like manufacturing of clothing and furniture, to poorer nations that are still in the process of industrial development. Thus, this progression of environmental clean-up occurring in conjunction with economic growth cannot be replicated indefinitely, because there will be nowhere to export waste and pollution intensive processes.

3. Industrial societies will continually produce new pollutants as the old ones are controlled.

Criticisms of the Criticisms!

Criticisms 2 and 3 above assume that ideas and technology are basically fixed and stagnant. For example, 2 assumes the only way to get rid of environmental waste is to export it. And 3 assumes that an increase in production will necessarily create more pollutants -- that isn't necessarily true.

The one resource that environmentalism often ignores is a great idea from a human being (invention, technology, process, etc.)!

Externalities - When costs or benefits fall on people who did not create them - there might be problems.

Remember when we discussed efficiency -- in order to determine if a production process is actually being efficient, all costs must be considered -- including both internal and external - and of course, whether or not what is being produced has value! So let's discuss external costs (and benefits) in more detail.

Externality (or external cost or benefit): the impact of one person's actions on the well-being of a bystander (the cost or benefit is created by Bob, but Betty is the one who bears the cost or receives the benefit).

You do something to benefit yourself but in the process cause a cost or benefit for someone else. So the cost or benefit is "external" to you.

Positive Externality:

Negative Externality:

Examples:

Economists usually talk about: Internalizing the Externality - when the party causing the externality must take the cost into account (pay) if it is a negative externality or when the party causing the externality is compensated for creating it (gets paid) if it is a positive externality.

This will (theoretically) lead to a decrease in negative externalities and an increase in positive ones.

Why? If a negative externality is “internalized” – the person creating it has to pay a higher cost for doing the activity and will therefore do less of it.

Example:

If a positive externality is “internalized” – the person creating it will be “paid” more for doing it and therefore will do more of it.

Examples of different kinds of externalities -

Negative Externalities in Production:

Positive Externalities in Production:

Negative Externalities in Consumption:

Positive Externalities in Consumption:

Of course - sometimes we can't determine who is causing the externality - or we don't discover the externality until after those who created it are gone.

So what are ways to internalize?

Private (Non-coercive) Solutions Toward Externalities:

1. Assign property rights and allow voluntary agreements or contracts: if property rights exist and if private parties can bargain they can often solve the problem of externalities on their own.

Actual fly-fishing/farmers example:

Farmers own farm land and have property rights in some of the water in a river.

Fisherman also have property rights in the use of the river.

The farmer's use of the water created a negative externality for the fishermen (too little water, fewer fish) - so they bargained. The fishermen paid the farmers not to farm.

Or of course, once property rights are assigned - invading another's property or person can be taken care of under the criminal legal system. For example, fraud or assault. Or Strict Liability! If you harm another person or another person’s property – you are liable!!

Problem: Property rights not being clearly defined, or difficult or impossible to determine who is damaging another's property. Or – when property is “public” – more on that later.

2. Moral codes/social sanctions:

Problem: not everyone abides by moral codes.

3. Persuasion:

Problem: everyone can't be persuaded and/or negotiation costs can be high

4. Integration:

Problem: negotiation costs can be high or the cost of integration itself is too high.

5. Charities (positive externalities):

Problem: not everyone wants to give to charities

Public (Government) Policies Toward Externalities: (Problems with all of these - involves the use of force and Knowledge problems on the part of government regulators)

1. Regulation:

a. ban production processes

Problem: don't know if the costs outweigh the benefits (Knowledge Problem)

b. specify minimum air or water quality levels

Problem: what level is best? - and why try to go below it with better technology - kills incentives to come up with better ways of doing things (Knowledge Problem)

c. the government specifies what kind of technology is used

Problem: stifles innovation - again, kills incentives (Knowledge Problem)

2. Taxes and Subsidies:

a. tax those who pollute

Problem: hard to know who to tax sometimes - and certainly how much? (Knowledge Problem)

b. subsidize those who create positive externalities

Problem: hard to know who to subsidize - and certainly how much? (Knowledge Problem)

3. Tradable Pollution Permits (Cap and Trade):

Problem: What should the cap be? (Knowledge Problem)

NOTE: Another problem with all of these government solutions is political pressure from interest groups to achieve specific outcomes. These groups have political power – but do not bear the costs of what the government does. So the policy takes place – not because of sound theory and evidence – but because of special interest group pressure.

Because of this and knowledge problems - not knowing the lowest cost technology or the “costs” or “benefits” of individuals that derive from different options –

Economists in general will emphasize property rights as a way of internalizing externalities. Let's look deeper...

The Tragedy of the Commons

Property Right: The owner has the right to dispense with the property in a manner he or she sees fit, whether to use or not use, exclude others from using, or to transfer ownership. Property rights and incentives are very much related. With ownership rights -- if I can increase the value of my property - I can reap the rewards from doing so.

Common Resource: goods that are not owned by any one person - no one is excluded from its use.

Free Rider Problem: an individual reaps the benefits from free-riding, but the costs are spread among the whole group. So individuals have an incentive to free ride.

A person receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it - with common property, people have an incentive to "free ride" off of others - throwing trash on the beach in the hopes (or assumption) that someone else will pick it up. But if everyone is free riding...... what happens to the beach?

Tragedy of the Commons: common resources get used more than is desirable - even to the point of destruction. Each person wants to "free ride" off of others - and/or they want to use the property before someone else can.

Example from the Issues book: Codfish off the New England and Canadian coasts. Problem - the fish had to be hauled from the sea before property rights to it could be established. The result was over-fishing - each fisher could benefit by catching fish but the cost (fewer fish in the future) was spread among all fishermen. The catch dropped dramatically over a 30 year period - more than 75% (and the fish got smaller). As a result -- the cod fishing in that area is virtually gone.

Main Economic Solution to the Tragedy of the Commons: Property Rights

"It is important to remember this: Property rights generally are not something that government “grants” to people. They usually develop on their own." There are many examples.

History is full of examples of voluntary associations – all designed to bring order to competing claims before the formal claims process applied to the land.

Example from Native Americans:

Montagnais Indians and beavers –

Also, different colors on arrow tips to establish property rights in buffalos.