Evolution of Economic Thought

David Ricardo and J. S. Mill

David Ricardo – The Ricardian System

David Ricardo (1772-1823)

Life: Ricardo was the third of seventeen children. At age 14, after a brief schooling in Holland, Ricardo joined his father at the London Stock Exchange, where he began to learn about the workings of finance. This beginning set the stage for Ricardo's later success in the stock market and real estate.

Ricardo became interested in economics after reading The Wealth of Nations in 1799 on a vacation. This was Ricardo's first contact with economics. He wrote his first economics article at age 37 and within another ten years he reached the height of his fame.

Ricardo's work with the stock exchange made him quite wealthy, which allowed him to retire from business at the age of 42. He then purchased and moved to an estate in Gloucestershire in England.

In 1819 Ricardo took a seat in the British parliament. He held the post until the year of his death in 1823. Ricardo was a close friend of James Mill (father of John Stuart) who encouraged him in his political ambitions and writings about economics. There is evidence that some of the theories in Ricardo’s writings were actually those of James Mill. Other notable friends included Bentham and Malthus (with whom Ricardo had a considerable debate - in correspondence - over such things as the role of land owners in a society.

He died at Gatcombe Park at 51 years of age.

Most of the theories presented are from: On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817)

The Central Problem to Ricardo was distribution theory (to wages, to capital investment, etc.) and what effects changes in distribution have on capital accumulation and economic growth.

Basic Principles

Very much influenced by Adam Smith and others, his basic principles are:

Malthus population principle

The wage – fund doctrine

Classical rent theory

Diminishing marginal returns (vague)

Comparative Advantage (at least he is given credit for it)

Free Trade

Say’s Law

Wage Theory (this is part of his emphasis on distribution of resources)

The term wages are used by Smith and Ricardo to denote contractual payment for hired labor.

Basic to Ricardian Wage Theory was the distinction between the “market price” of labor and its “natural price.”

Market Price of labor = Supply and Demand of Labor

Natural Price of labor = subsistence wage

The natural price: was defined as the amount which enables the workers to subsist (survive) and to perpetuate without increase or decrease (as with Malthus).

That price (wage), expressed in real terms, was variable with different times and different regions.

The Market Price or S & D of labor (in the long run -- the market price and the natural price of labor were the same. In the short run, they could be different. More on this later).

Graph:

So what influenced the Demand and Supply of labor?

The Demand for Labor and the Wage Fund:

Elaborating the idea of a wage-fund, Ricardo regarded this as a more or less fixed aggregate of wage goods (so it was basically a real wage), a sort of predetermined share for labor in the national income. This fund was the main determiner of the demand for labor.

So Demand for Labor determined by overall progress – capital, productivity, profits etc. The more productivity in general, the greater the national income, the more labor can be paid, the higher demand for it and the higher wages paid.

If the wage fund eats up most of the profit, however, the capitalist won’t continue to produce, demand for labor goes down. So the more profitable capital was, the more demand for labor there was, and the higher wages were. But if too much of the revenue earned went to labor -- they would suffer in the long run from fewer jobs and lower wages. There needed to be a balance.

So Demand labor = f (productivity)

The Supply of Labor:

The Malthusian population theory provided the explanation for changes in the supply of labor.

Increase in population meant an increase in the supply of labor and was bound to lead to a decrease in wages (had to split the wage fund up among more people).

So Supply of labor generally speaking = f (population)

The wage rates of specific categories of workers were held to be determined by supply and demand.

Remember - Ricardo did not do the following graphical representation of his theories -- this is the modern interpretation.

So here is his analysis:

Assumption:

1) Capital increases in quantity and in value (prices and profits have increased), output increases and the demand for labor increases.

The demand for labor increases -- this increases the market price of labor AND the natural price of labor (since the price of goods and services have increased and profits have increased - the value of capital has increased -- therefore, we need a higher wage for subsistence - BUT we can support a higher population (movement along the supply curve of labor), so the natural rate of employment increases.

Graph:

The question: Will the increase in wage be permanent or not?

Depends on if prices and profits increase or not. If the value of capital increases, then it will be permanent, since that feeds into the wage (natural).

Natural wage = subsistence = f (prices and profits - the value of capital).

If prices and profits increase, the natural wage will increase as well.

On the other hand, if the amount of capital increases - but not its value, then this will not be permanent. Demand for labor will shift back down - and we will return to the lower natural price of labor.

Graph:

So again, the price of labor (wage), expressed in real terms, was variable with different times and different regions - depending upon the overall productivity (value of capital) in that time and region! But the ultimate check on how far the wages would increase (profit, etc.) was the amount of land available in the region. More on this later.

Controversy over Ricardo’s theory of Value:

Some interpret it as a strict labor theory of value.

However, others want to characterize Ricardo’s theory of value as a “real-cost” theory, where labor is the most important factor but capital is important as well.

It seems he may have used both definitions, depending upon what he was trying to explain.

To Ricardo the relation between value and labor time expended in production was straightforward:

“Every increase of the quantity of labor must augment the value of that commodity on which it is exercised as every diminuation must lower it.”

He added several qualifications to this, but sometimes side-stepped them to use a simple labor theory of value.

The Theory of Rent and Diminishing Returns to Land

Referring to Smith’s observation that the supply of land, the natural factor of production, could not be increased when the prices of agricultural products were rising,

Graph (not from Ricardo):

Ricardo argued that:

Rent would accrue only when the price of agricultural products was in excess of their costs.

Therefore an increase in prices of agriculture leads to an increase in rent.

No rent accrued to land if the yield was produced at the highest costs just covered by the prevailing price.

A Somewhat Fuzzy Concept of Diminishing Returns: He discussed diminishing returns to land.

Rents were determined by the differences between the values of agricultural products obtained by the employment of equal quantities of capital and labor and costs of production.

Rent = Value of Agriculture - Costs of Production

Such differential rents were bound to rise with each increase in population:

Increase Population - Increase demand - Increase prices of agriculture - Increase rent.

This lead to the cultivation of land of poorer quality than before, or to a more intensified cultivation of land. And this lead to an incremental (marginal) decrease in output.

Land, labor and capital were all homogenous factors to Ricardo.

His diminishing returns was not clear - but it has been interpreted (at least one interpretation) as: equal successive (marginal) increments of the variable factor yield decreasing increments of the product (that is, as we add one marginal variable factor, we will get a marginal decrease in output).

Example:

Comparative Advantage – Free Trade

Originally suggested by Robert Torrens, British economist, The Economist Refuted (1808) and An Essay on the External Corn Trade. But, according to Rothbard and others, it was really James Mill that fully developed the theory in "Colonies" for the Encyclopedia Britannica (1818).

In order to determine the advantages accruing from international trade, it was not appropriate to base the comparisons on absolute values. But instead, should be based on opportunity costs (comparative values).

Rather, it was necessary to define the relationship which existed in each country between the labor costs of the various products, and to use these ratios for purposes of comparison.

The results of these comparisons could lead to the conclusion that the international exchange of certain goods was profitable even though the imported commodities could be produced domestically at less absolute costs then in the exporting country.

So here is Ricardo on this:

|

"It is not, therefore, in consequence of the extension of the market that the rate of profit is raised, although such extension may be equally efficacious in increasing the mass of commodities, and may thereby enable us to augment the funds destined for the maintenance of labour, and the materials on which labour may be employed. It is quite as important to the happiness of mankind, that our enjoyments should be increased by the better distribution of labour, by each country producing those commodities for which by its situation, its climate, and its other natural or artificial advantages, it is adapted, and by their exchanging them for the commodities of other countries, as that they should be augmented by a rise in the rate of profits." On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Chapter 7. |

The example dealt with wine produced in Portugal for cloth in England.

Ricardo and Say’s Law

Remember that Say's law of markets tried to show that a "general glut" or over supply of goods would not happen in the long run if markets could clear on their own. Prices would fall, increasing demand and/or profits would fall, decreasing supply.

The major figure on one side of the debate was our old friend, Thomas Malthus. He argued that crises were a result of a "general glut" of goods (very Keynesian). The production of goods could outrun the ability or desire of people to purchase these goods, and it was this oversupply or under-consumption that led to an economic crisis.

On the other side of the debate were Ricardo, James and John Stuart Mill, and Say. Those ideas that are called Say's Law were developed by all of them in their attempt to show that the under-consumption thesis was wrong.

Say’s Law was dominant in Ricardo’s analysis.

An economic slump (stationary state) was not due to under-consumption, but not enough productivity. Productivity must take place for inputs to earn income, then they can consume. Investment and capital were key.

The less desirable stationary state was viewed as the inevitable outcome of economic history.

Classical (Ricardian) economic analysis was long run – based on a few simple assumptions. Key elements were:

(1) Malthusian population theory (as you can see in his analysis of the stationary state).

(2) The principle of diminishing returns to agriculture

(3) The wages-fund doctrine based on production.

So we start with:

K and I high, Wages are high (K - capital, I = investment)

|

Growing population

|

Pressure on food supply

|

Diminishing returns to K and L in agriculture (L = labor)

|

Utilize inferior plots of land

|

Costs of productivity increase, profits decrease

|

Decrease K and I as we approach stationary state.

To sum:

In an expanding economy the level of investment and wages is high and growing. Capital accumulation is taking place.

But high wages induce population growth, and pressure on food supply – fixed land – lead to diminishing returns to capital and labor in agriculture and the necessity of utilizing inferior grades of land to feed a growing population.

Consequently, this leads to the costs of production increasing and profit decreasing.

Decreasing profits leads to decrease capital accumulation and investment as the stationary state is approached.

As Rothbard puts it: "For Ricardo the key to the stifling of economic growth in any country, and especially in developed Britain, was the 'land shortage,' the contention that poorer and poorer lands were necessarily being pressed into use in Britain. In consequence, the cost of subsistence kept increasing, and hence the prevailing (which must be the subsistence) money wage kept increasing as well. But this inevitable secular increase of wages must lower profits in agriculture, which in turn brings down all profits. In that way, capital accumulation is increasingly dampened, finally to disappear altogether."

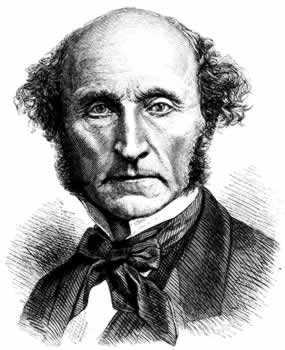

John

Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

Mill refused to study at a university. Instead he followed his father to work for the British East India Company until 1858. Between the years 1865-1868 he served as Lord Rector of the University of St. Andrews. During the same period, 1865-8, he was an independent Member of the Parliament. During that time, Mill advocated easing the burdens on Ireland, and became the first person in parliament to call for women to be given the right to vote.

In 1851, Mill married Harriet Taylor after 21 years of an intimate friendship (while she was still married). Taylor was married when they met, and their relationship was close during the years before her first husband died. Brilliant in her own right, Taylor was a significant influence on Mill's work and ideas during both friendship and marriage. His relationship with Harriet Taylor reinforced Mill's advocacy of women's rights. He cites her influence in his final revision of On Liberty, which was published shortly after her death, and she is referenced in The Subjection of Women. Taylor died in 1858, only seven years into her marriage to Mill.

Mill died in France in 1873 and is buried alongside his wife (in France).

Major Works:

J.S.

Mill was much more than an economist – his works include:

A System of Logic (1843)

Principles of Political Economy (1848)

On Liberty (1859)

Considerations of Representative Government (1861)

Utilitarianism (1863)

The Subjection of Women (1869)

He

wrote on method, utility, individual freedom and representative government, etc.

As with Ricardo - we see some of modern-day analysis in Mill.

On Method

According to Mill, in the social sciences the empirical, or inductive, method could not be relied on solely – since causes of social phenomena are often complex and interwoven and effects not easily distinguishable from one another (going from specific to general).

So deduction was a check on the errors of causal empiricism (general to specific).

And

facts are a check on deduction.

So

he wanted a balance between the two.

Ceteris

Paribus:

J.S. Mill also showed the importance of the ceteris paribus clause

as an instrument of deductive reasoning which enabled the student to determine

separately the effects of one cause out of a number of conflicting causes.

Benthamite utilitarian philosophy was strengthened by J.S. Mill through the introduction of the concept of “economic man” – (which linked human behavior to the economy) an individual who is

“determined by the necessity of his nature to prefer a greater portion of wealth to a smaller” and is “able of judging of the comparative efficacy of means of obtaining the possession of wealth.”

A

maximization principle.

But he was aware of the purely hypothetical nature of his concept.

How can an economist know if another has maximized?

Indeed, how can the “economic man” know?

Mill’s Principles of

Political Economy was his most influential work in Economics.

Separated

the laws of production and the laws of distribution.

The

laws of production

were unchangeable and governed by natural laws.

But

the laws of distribution were a matter of changing

values, mores and social philosophies and tastes….

Therefore malleable and need history as well as economics to understand

them.

On

Production:

Capital and capital accumulation were very important as with Smith, Say, Ricardo, etc.

Given

Say’s Law, employment and increased

levels of employment and output are dependent

on capital accumulation and investment of capital.

Unemployment

of resources – except in the short run – was not possible because of Say’s

Law.

Mill added to the Equilibrium interpretation of Say’s Law:

The

Circular Flow Diagram:

Saving

leads investment, so a general glut was impossible.

Saving

(S)

a function of the interest rate.

Investment

(I) a function of the interest rate.

Therefore, as long as it was flexible S = I in the long run and there would not be a leakage to the system.

This is where Mill also discusses the theory now known as "crowding out." (from your reading)

Productivity Issues of Government Debt

Mill has an opportunity cost argument:

Mill asks, "Did the government, by its loan operations, augment the rate of interest? . . . So long as the loans do no more than absorb this surplus [of capital accumulation], they prevent any tendency to a fall of the rate of interest, but they cannot occasion any rise."

If interest rates do increase: Mill says, " . . . this is positive proof that the government is a competitor for capital with the ordinary channels of productive investment . . . " Therefore, when the government borrows money from the public -- that money could have been invested by the private sector and increased productivity. This is a large opportunity cost of government borrowing according to Mill.

The model today (Mill did not graph it):

Graph:

Mill's exceptions to this cost of government borrowing:

1. If the capital comes from foreign countries:

2. If the capital would not have been used in productive investment (opportunity cost low). Mill's way of answering this was if the interest rate was driven up or not when the government entered the loanable funds market.

On Economic Growth and the Stationary State

Limits to economic growth:

(1)

Diminishing returns to

agriculture

(2)

Declining incentive to invest

(due to drop in profitability)

Like

Ricardo – the economy went from a progressive state to a stationary

state. But Mill did not believe this

stationary state was undesirable – once it is reached, problems of

distribution could be evaluated and social reforms put in place.

“It

is scarcely necessary to remark that a stationary condition of capital and

population implies no stationary state of human improvement.

There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and

moral and social progress; as much room for improving the Art of Living, and

much more likelihood of its being improved, when minds ceased to be engrossed by

the art of getting on”

(Principles

p. 751).

To

Mill this stationary state in economics became kind of a “utopia” – having

achieved affluence, the state could get on with solving the problems that really

matter – equality of wealth and opportunity.

Mill’s

Other Theoretical Advances

Supply

and demand

- -the first clear British contribution to static equilibrium price

formation was developed by Mill. Using

verbal analysis, however.

Here

we get the formulation of Demand and Supply schedules showing the functional

relation between Price and Quantity D and Quantity S, ceteris paribus.

Went

from a ratio relationship between S and D to an equation form:

(By

value he means price)

“A

ratio between demand and supply is only intelligible if by demand we mean

quantity demanded, and if the ratio intended is that between the quantity

demanded and the quantity

supplied. But again, the

quantity demanded is not a fixed quantity, even at the same time and place; it

varies according to the value; if the thing is cheap, there is usually a demand

for more of it than when it is dear.” (Principles p. 446).

“The

idea of a ratio, as between demand and supply, is [therefore] out of place, and

has no concern in the matter: the

proper mathematical analogy is that of an equation.

Demand and supply, the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied, will

be made equal. If unequal at any

moment, competition equalizes them, and the manner in which this is done is by

an adjustment of the value. If

the demand increases, the value rises; if the demand diminishes, the value

falls; again, if the supply falls off, the value rises; and falls if the supply

is increased” (Principles p. 448).

Mill’s

Neo-Classical Contributions

He

was “in direct line to Alfred Marshall” who is the father of Neo-Classical

analysis.

Mill

was also ahead of Leon Walras (in general equilibrium

theory)

With

his price adjustments that establish conditions of reciprocal equilibrium….markets

adjusting to each other and all achieve equilibrium.

Mill’s

Normative Economics

J.S.

Mill was a zealot in the matter of social reform, but in a way that would

preserve individual freedom.

In

On Liberty Mill:

“The

only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a

civilized community against his will” is to prevent harm to others.

“After

the means of subsistence are assured, the next in strength of personal wants of

human beings is liberty.”

Mill

was very concerned with greater equality of wealth and opportunity:

thus he wrote with great concern on issues such as wealth redistribution,

equality of women, rights of laborers, consumerism and education.

Examples:

On

inheritance and equality:

Were

I framing a code of laws according to what seems to me best in itself, without

regard to existing opinions and sentiments, I should prefer to restrict…what

any one should be permitted to acquire, by bequest or inheritance.

Each person should have power to dispose by will of his her whole

property; but not to lavish it in enriching some one individual, beyond a

certain maximum, which should be fixed sufficiently high to afford the means of

comfortable independence. The

inequalities of property which arise from unequal industry, frugality,

perseverance, talents, and to a certain extent even opportunities, are

inseparable from the principles of private property, and if we accept the

principle [as Mill did] we must bear with these consequences of it; but I see

nothing objectionable in fixing a limit to what any one may acquire by the mere

favour of others; without any exercise of his faculties, and in requiring that

if he desires any further, he shall work for it (Principles, pp. 227-229).

Mill

attacked wealth accumulation for its own sake – breaking from the other

classical economists to a point –

economic

distribution is as important or more so than economic growth.

To

Mill social reform was not simply the destruction of oppressive institutions –

Rather

it consists in …”the joint effect of the prudence and frugality of

individuals, and of a system of legislation favoring equality of fortunes, so

far as is consistent with the just claim of the individual to the fruits,

whether great or small, of his or her own industry” (Principles, p. 749)

So

he wanted to: distinguish

between income and wealth:

On the Relationship Between Men and Women:

Many believe that his friend/wife contributed to his writings (she was not allowed to publish under her own name, being a woman). Most especially, Mill gave her credit for adding to The Subjection of Women:

"What marriage may be in the case of two persons of cultivated faculties, identical in opinions and purposes, between whom there exists that best kind of equality, similarity of powers and capacities with reciprocal superiority in them---so that each can enjoy the luxury of looking up to the other, and can have alternately the pleasure of leading and of being led in the path of development---I will not attempt to describe. To those who can conceive it, there is no need; to those who cannot, it would appear the dream of an enthusiast. But I maintain, with the profoundest conviction, that this, and this only, is the ideal of marriage; and that all opinions, customs, and institutions which favour any other notion of it, or turn the conceptions and aspirations connected with it into any other direction, by whatever pretences they may be coloured, are relics of primitive barbarism. The moral regeneration of mankind will only really commence, when the most fundamental of the social relations is placed under the rule of equal justice, and when human beings learn to cultivate their strongest sympathy with an equal in rights and in cultivation.

From The

Subjection of Women, Chapter 4

On Taxes and Equality:

As you saw in the reading, equality was also an issue with Mill with respect to taxes. Somewhat similar to Smith, he said that taxes should be:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Equality of burden or sacrifice was important to Mill. If someone had a great ability to produce, then they could pay more taxes because the "sacrifice" would not be as high to them as to someone without the ability.

Government

and Laissez-faire

Mill

saw necessary functions of government and optional functions.

Necessary

– power to tax, coin money, est. system of

weights and measure, protection against force

and fraud, contract enforcement, protect

property rights, provide of “public goods.”

He

did say that laissez-faire should be the rule – any departure from it “unless

required by some great good, is a certain evil.”

But his exceptions are many.