ECON 369

Outline Twelve:

Alternative Means of Financing Government Expenditures

Sources:

Various

(see citations in the text).

There are typically three ways of financing government spending:

taxes, debt, and money.

Some governments also charge for the use of

certain services as we have discussed. For example, user fees for national

parks, toll roads, and charging for public transportation are also used.

And governments can sell off assets, e.g.,

buildings, land, bombers, etc.

Can you think of others?

Common

Wisdom: If the economy is stronger than expected, federal government

revenues increase and expenditures decrease. If the economy is weaker than

expected, federal government revenues decrease and expenditures increase.

Financing tends to be vastly dominated by taxes,

bonds, and money. We have already discussed taxes. So now let's

discuss debt and money.

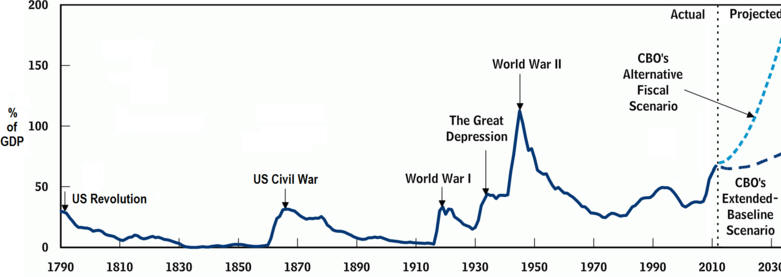

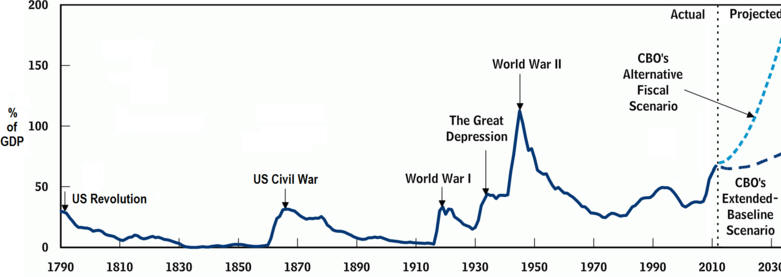

The Chart Below

shows the pattern of US Federal debt since 1790 as a percent of GDP. The

government dramatically increased the stock of debt to finance its wars. This

was usually followed by a long period of declining debt as the US paid off the

debt incurred during the war. It should be noted that

the chart does not include intergovernmental bonds, i.e., bonds transacted

between agencies in the government. One of the main sources of these bonds is

the social security trust fund, which began accumulating in the early 1980s.

Let's review some terms:

How does the government go into debt?

Government Debt vs. Private Debt (private businesses engage in both equity

financing and debt financing - know the difference) -- the government simply

goes into debt to pay for its expenditures.

Treasury

Bonds or Bills:

Balanced

Budget:

Budget Surplus:

Budget Deficit:

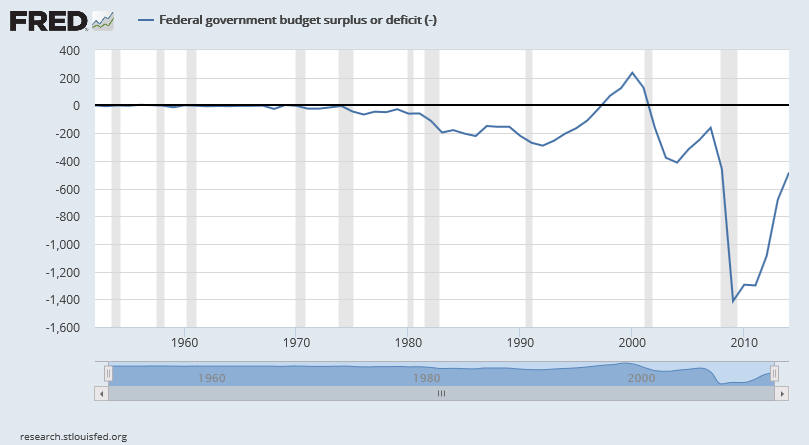

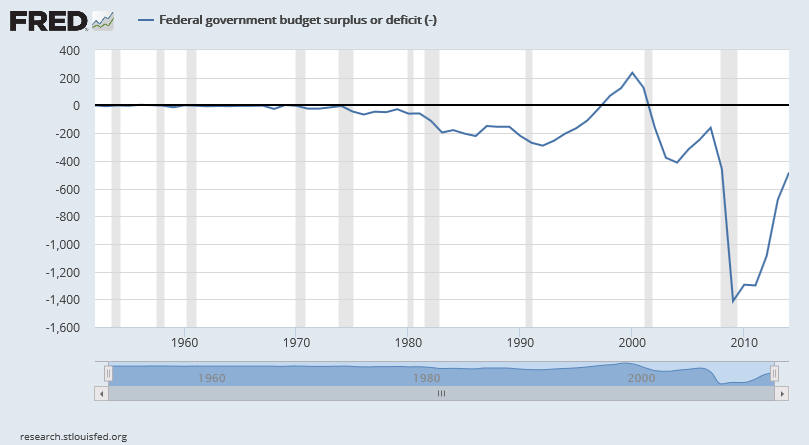

Budget

Deficit: (Billions of Dollars)

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M318501A027NBEA

Federal or

National Debt

- the total amount borrowed from investors to finance deficit spending by the

federal government. The accumulated borrowing from all past deficits minus debt

that has been retired with past surpluses.

Gross

National Debt - Value of all outstanding government securities of any

maturity held by private investors or in government accounts.

Net

National Debt - subtract out the debt held by the federal government

(intra-governmental holdings)

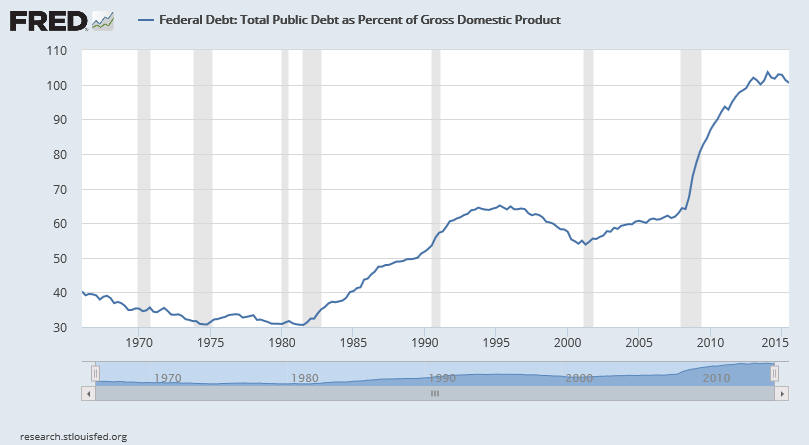

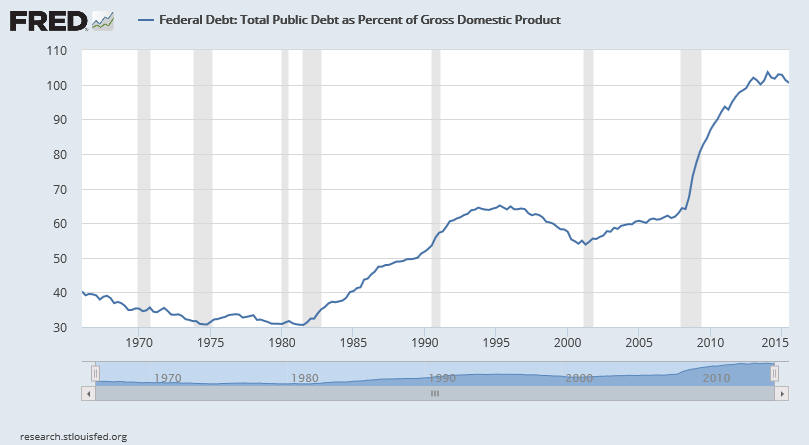

The Debt Clock

Debt as % of GDP

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/GFDEGDQ188S

Who holds the debt?

The

Treasury Bulletin, available online from the Financial

Management Service categorizes ownership of U.S. Government

securities by types of investors.The Debt Held by the Public is all

federal debt held by individuals, corporations, state or local

governments, foreign governments, and other entities outside the

United States Government less

Federal Financing Bank securities. Types of securities held by

the public include, but are not limited to,

Treasury Bills, Notes, Bonds, TIPS, United States Savings Bonds,

and

State and Local Government Series securities.

Here's a picture of it:

https://www.nationalpriorities.org/campaigns/us-federal-debt-who/ )

There are two basic categories of debt owners: 1) the

public, which includes foreign investors and domestic investors

and, 2) federal accounts, also known as "intragovernmental

holdings.

Debt Held by the Public: Domestic Investors

Public debt is also held domestically. Domestic

private investors - which includes regular American citizens as well as

institutions like private banks.

The U.S. Federal Reserve Bank buys and sells

Treasury bonds as part of its work to control the money supply and set

(manipulate)

interest rates in the U.S. economy, so they hold some of the debt (about 13%).

Finally, U.S. state and local governments have

also lent money to the federal government.

Debt Held by the Public: Foreign Investors

About 34 percent of the U.S. debt is held

internationally by foreign investors (i.e. foreign governments,

foreign institutions, and individual people in foreign countries)

who buy U.S. Treasury bonds as investments.

Debt Held by Federal Accounts (intragovernmental

holdings)

Debt held by federal accounts is not considered

public debt - it is the amount of money that the Treasury has borrowed

from itself. That may sound funny, but it means that the Treasury

borrows surplus money from one trust fund and gives it to another trust

fund. For example, the Treasury might borrow money from Social

Security to finance current government spending in another area. At a

later date, the government must pay that borrowed money back.

(Note: The Federal Reserve is not

counted as "debt held by federal accounts" because the Federal Reserve

is considered independent of the federal government - well at least its

budget is!

What

about New Money

U. S.

Treasury vs. The FED (central bank of the U.S.):

Monetizing the Debt and Inflation:

The Economic Analysis

Probably

the most prolific economist on the topic of government debt:

James Buchanan

(all of the following quotations are by Buchanan). Beginning with his Public

Principles of Public Debt, published in 1958.

Buchanan says

(from your reading):

1. The primary real burden of a public debt is shifted to

future generations.

2. The analogy between public debt and private debt is fundamentally correct.

3. The external debt and the internal debt are fundamentally equivalent.

1. Discussion

of the problem of the burden on future

generations. Moral dimension to the debt. Buchanan disagreed with

Keynesian economist Abba Lerner, who stated: the "national debt is not a burden on posterity

because if posterity pays the debt it will be paying it to the same posterity

that will be alive at the time when the payment is made." In other words, the

same group of people will be paying interest on the debt -- to themselves (those

that hold the bonds). Taxed one day, receive interest the next. So

the "burden" of the debt falls on those who own the government bonds.

So quotation

from reading: "perhaps the best clue provided in a statement from Brownlee

and Allen: 'The public project is paid for while it is being constructed

in the sense that other alternative uses for these resources must be sacrificed

during this period.'"

As Buchanan

states -- this is obviously true. But, "the mere shifting of resources

from private to public employment does not carry with it any implication of

sacrifice or payment."

Buchanan's argument:

Bob buys a government bond (his choice) because in

his mind this is a good exchange -- he lends the money today in order to earn

interest in the future. He benefits from this exchange. He does not

undertake the burden or sacrifice of a given public project even if the money he

lends is used for that particular public project.

Bob does give up a current command over his

resources -- but it is his choice to do so -- he freely does this in order to

gain the interest.

Putting aside the effects of the public spending --

no other individuals in the economy are affected at this time.

The problem is that the argument is only

concerned with macro-economic variables and not with individual human beings!!

We must break down the economy into individuals (or families) in order to

understand where the burden of deficit spending falls.

Buchanan: "The public project is

purchased, and paid for, by those individuals who sill be forced to give up

resources in the future . . . ." "The burden must rest, therefore,

on the taxpayer in future time periods and on no one else. He now must

reduce his real income to transfer funds to the bondholder, and he has no

productive asset in the form of a public project to offset his genuine

sacrifice."

If the public expenditure was wasteful (or the

benefit from it only gained by individuals at the time of the public

expenditure) then there is no further analysis. However:

"If the debt is created for productive public

expenditure, the benefits to the future taxpayer must, of course, be compared

with the burden so that, on balance he may suffer a net benefit or a net

burden."

In other words, if the expenditure was made on

something that might still be around to benefit future taxpayers -- then that

has to be considered. But again, this should be looked at on an individual

basis. If the money was spent on a highway in Colorado - and a federal

taxpayer in New York never visits Colorado -- he has no gain!

So he attacked the

notion that "we owe it to ourselves." His use of subjective cost

concepts was important here in demonstrating that we do not owe the debt to

ourselves, but that the burden is shifted to future generations.

Individual subjective cost analysis vs.

aggregate "welfare" analysis.

So are Deficits OK -- or do they really do harm to the economy?

Remember that

is was Keynes, in the 1930s, who suggested that deficits be used as a policy

tool (not just to finance war or other abnormal spending).

Keynesians

more typically today:

On the perpetual question of whether budget deficits matter and if so why, the

Neo-Keynesian answer distinguishes between

cyclical and structural deficits.

Structural

deficits

might

matter because they decrease savings, crowd out private domestic investment and

reduce future national income (explained below).

But the

automatic tendency of tax collections to fall and government transfers to rise

during an economic downturn, creating larger deficits in the Federal budget,

serves as a vital economic shock absorber that cushions private spending and

mitigates fluctuations. Remember, to a Keynesian, spending (aggregated demand)

is what drives an economy. So cyclical deficits are OK -- fiscal policy to

manipulate the economy is OK.

Buchanan's

Response

(and that of others) was to bring back the Classical Model of Crowding Out.

To him (and others) why the government is deficit spending doesn’t matter:

Crowding

Out

When the

government borrows, it enters the loanable funds market as a borrower (demander

of savings). This increase in demand drives up interest rates -- making

borrowing by private investors more expensive -- thereby decreasing productive

private investment.

Government

spending is not as productive as private investment - hence there is a decrease

in the overall pie!

What are Keynesians saying today about "crowding

out?"

Again -- if deficits are structural, than even

Keynesian might agree that large deficits might harm economic growth.

However, today they are saying that due to the large amount of excess reserves

in banks (due to expansive monetary policy by the FED), there is no crowding

out. In other words -- the FED has increased the money supply such that

the supply of loanable funds (although NOT from real savings) -- are high enough

to offset any increase in the demand for loanable funds - thus the interest rate

has not increased.

Plus -- if the deficits (and the debt) are an issue

-- the solution is to tax the rich. Why? Because the rich will pay

the taxes out of savings, not consumption -- therefore, aggregate demand will

not suffer.

What About Savings?

The argument then centered on (and still does

in some circles) the Ricardian Equivalence Theorem: farsighted,

rational taxpayers would be indifferent to the timing of taxes. That is, they

would treat deficits as equivalent to higher future taxes and surpluses as

equivalent to lower future taxes. Therefore, with deficits, taxpayers would

save now in order to pay the future taxes -- bringing interest rates back down.

Deficits would, therefore, not matter with respect to economic growth, etc.

David Ricardo

proposed this in the 1800's and then himself identified several reasons why this

"equivalence" may fail:

a. How much

should taxpayer's save now for the future?

b. Will

taxpayers really anticipate the higher future taxes?

c. Some

taxpayers may think the future taxes will be levied after they are dead, so why

save now?

d. Some

taxpayers may think the future taxes will come after they are retired -- so they

will fall on the next generation of workers - so why not let them deal with it?

Let the next generation pick up the tab (i.e., tax)!

Does Ricardian Equivalence actually hold in the world as it is? That's an

empirical question, and there is an ongoing debate among economists over which

side's evidence is weaker.

2. With

respect to the analogy between private debt

and public debt - Again - "When an internal debt is created, resources for

public use are withdrawn from private uses within the economy. Therefore,

the creation of debt and the correspondent financing of the public project does

nothing toward increasing or adding to the wealth of the society. This is, of

course, fundamentally correct as a first approximation and requires no difficult

reasoning for its comprehension."

In both public

and private debt -- there is an opportunity cost of the resources used to

finance the debt. This is the correct part of the analogy.

However, the government

borrows but does not invest or increase productivity in order to pay the

interest on the debt -- and there is an opportunity cost of those

resources -- they are "withdrawn from the private uses within the

economy." This is just a redistribution of the pie -- not creation of the

pie.

This is a fundamental difference between private and public debt:

When a

private business borrows to finance its operations, it uses those

resources to produce more wealth in society and pays back the debt with

interest with the new

wealth creation (or it goes out of business). The pie gets larger in order

to finance the private debt.

Is it possible that the public debt does increase

the pie -- yes, but not anywhere as likely as with private debt. Rules -

Incentives - Actions - Outcomes.

3. With

respect to: if the

debt is held outside of the issuing jurisdiction, it is called external;

if it is held within the jurisdiction, it is called internal - are

these fundamentally equivalent?

The argument that is given by those

who say that external and internal debt are different claim that in one case

(internal) - interest on the debt is paid by taxpayers within the jurisdiction

-- but they are also the lenders who will gain the interest - so it is a wash,

so-to-speak. On the other hand, with external debt -- the interest is paid

by taxpayers within the jurisdiction, but the interest is going to those outside

of the jurisdiction.

In both

cases the jurisdiction borrowing must pay the interest on the loan. But,

again

Buchanan didn't want to aggregate the community, but instead looked at

individuals -- so, not all who pay taxes

(to pay the interest on the public debt)

will be gaining interest (will own bonds).

So, in the case of internal debt, can't say it's a wash.

In the case of external debt, certainly isn't a wash.

So let's end

with

Buchanan's public choice focus on the erosion of

“inherited

traditions of discipline”

that held deficits in check -

"If you

recognize the natural proclivity of democratic politics to generate

deficits, you recognize that we did have a constitutional norm against deficits.

It was basically a moral norm:

It was a 'sin' to create deficits prior to the

Keynesian period. If you remove that moral norm you have this natural

proclivity." (Sep. 1995 - from an interview published in The Region,

a publication of the Woodrow Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis).

He later

maintained, that citizens will typically favor deficit financing because:

"Constituents enjoy receiving the benefits of

public outlays, and they deplore paying taxes. Elected politicians attempt to

satisfy constituents." (The Moral Dimensions of Debt Financing" in

Fink and High, 1987).

Let's

Review our Public Choice Theory as to why we have such large government deficits

- Think about it: How can the government debt be financed?

a. Higher

taxes

b. Monetize

the debt - higher taxes through inflation

c. Cut

spending - use the surplus to pay

d. Sell off

government assets - like the Lincoln Memorial

e. More debt

- the most politically expedient (you can buy more votes with deficit

spending)

Rather than making the burden obvious, politicians prefer to borrow for now and

to leave us all to guess about just what will happen after election day.

(from

Do Deficits

Matter?

by Lawrence H. White and Roger Garrison).

Buchanan's Solution:

Balanced Budget Amendment

-- constitutional amendment requiring government to spend no more than it

collects in tax revenues. Is it feasible?

Or maybe even better -- not just a Balanced Budget Amendment, but also a

Spending Limit Amendment!

Buchanan:

"I was influenced by the Swedish economist Wicksell, who said if you want to

improve politics, improve the rules,

improve the structure. Don't expect politicians to behave differently. They

behave according to their interests."

(Sept. 1995 - from an interview published in The Region, a publication of

the Woodrow Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis).

Can you tell I studied under

Buchanan? RULES - INCENTIVES - ACTIONS - OUTCOMES! AND

POLITICIANS ARE NO DIFFERENT FROM ANYONE ELSE!

DO

ICE THIRTEEN