ECON 378

Avoiding Bad Arguments and Reasoning

Source: Richard L. Epstein, Critical Thinking

Concealed Claims

a) Where is the argument?

Have you ever had someone try to convince you of something by their choice of words and not their argument?

One example of this is when someone tries to close off the argument by making a definition that should be the conclusion.

Example: If a person defines “abortion” to mean “the murder of an unborn child,” he or she has made it impossible to debate whether abortion is murder and if a fetus is a human being. The conclusions are built into the definition. But there is no argument.

There are lots of ways people can conceal their claims through their choice of words.

Slanter – any literary device that attempts to convince by using words that conceal a dubious claim.

Be aware of them and point out that there is no argument in their words.

b) Loaded questions: a question that conceals a dubious clam that should be argued for rather than assumed.

Example: I was speaking to some of my colleagues about infusing research into my classes. I said something like, the students might enjoy writing some cases that could be presented at conferences. One of my colleagues said, “Why would anyone not think of students first when deciding what to do in the classroom?”

What was the assumption of his question?

Here are some more loaded questions:

Why don’t you love me anymore?

Why can’t you dress like a lady?

The best response to a loaded question is to point out the concealed claim and begin discussing that.

c) What did you say?

1. Making it sound nasty or nice

Labels conceal claims. For example:

In an ad you might read that an apartment is “quaint” – what that really means is small.

Someone might describe a janitor as a “sanitation engineer.”

These are Euphemisms – words that makes something sound better than a neutral description.

What about:

Calling a stewardess a “waitress in the sky.”

Or what comes to mind when you hear the words “freedom fighter” vs. “terrorist?”

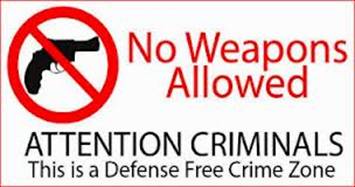

These are Dysphemisms – words that makes something sound worse than a neutral description.

You don’t want to get rid of every pleasant or unpleasant description in your writing and speech. But just be aware of misuses where we’re being asked to buy into dubious concealed claims.

Words can sway people even when no argument is presented.

2. Downplayers and up-players

Example: The President and Congress managed to ensure that only two million jobs were lost in the economy this year.

“Only” is downplaying the significance of a very disagreeable outcome.

And “managed to” is up-playing the significance of the effort.

A downplayer – word or phrase that minimizes the significance of the claim.

An up-player – word or phrase that exaggerates the significance.

Extreme version – hyperbole.

Betty: I’m sorry I’m late for work. I had a terrible emergency at home.

Boss: Oh, no. I’m so sorry. What happened?

Betty: I ran out of hair spray and had to go to the store.

People also downplay by using quotes or a change in voice (when speaking):

Example: He got his “degree” from a beauty school.

Bottom line: Watch the words you use – we often downplay or up-play without even thinking about it. And pay attention to the words used by others. When they downplay or up-play, what are they trying to claim without giving an argument?

3. Where’s the proof?

“By now you must be convinced what a great law this is. It’s obvious to anyone. Of course, some people are a little slow. But surely you see it.”

Did I prove that the law I was talking about is great? No.

I just made it sound as though it is obvious – so if you don’t see it, it is your fault.

By using the words “obvious,” “some people are a little slow,” “surely,” and “must be convinced” I was browbeating you into believing something that I have not shown any evidence or theory that it is true.

Proof substitute – a word or phrase that suggests the speaker has a proof, but no proof (or evidence and theory) is actually offered.

When someone tells you something is “obvious” – be aware!

Ridicule – this is one of my pet peeves – it is a nasty form of proof substitute.

“That’s so obviously wrong it is laughable.”

Or even simply laughing at someone’s statement – the hidden claim is that what was just said is not even worth considering – it is laughable.

No argument is given as to why it is laughable. This is a very arrogant way of trying to convince people that no argument is even necessary.

Words alone don't constitute proof – or even an argument (as some things cannot be “proved” but can be argued).

4. Innuendos

Any concealed claim is an innuendo (an allusive remark or hint)

But usually they are used for concealed claims that are really unpleasant.

Betty: Where are you from?

Bob: New York.

Betty: Oh, I’m sorry.

The concealed claim is “You deserve pity for having had to live in New York.”

Again, there is no argument given as to why living in New York deserves pity.

d) Slanters and Good Arguments

Remember – a slanter is any literary device that attempts to convince by using words that conceal a dubious claim.

You will probably be tempted to use them. Don’t.

They turn off those you want to convince. Worse, though they may work for the moment, they don’t stick. Without reinforcement, the other person will remember only the joke or jibe.

A good argument can last and last – the other person can see what you are saying clearly and reconstruct it.

And if you use slanters instead of arguments, your opponent can destroy your points not by facing your real argument but by pointing out the slanters.

If you reason calmly and well you will earn the respect of the other person, and may learn that the other person merits your respect, too.

Too Much Emotion

Appeals to Emotion

Emotions do and should play a role in our reasoning: We cannot even begin to make good decisions if we don’t consider their significance in our emotional life.

But that does not mean we should be swayed entirely by our emotions.

An appeal to emotion in an argument is just a premise that says, roughly, you should believe or do something because you feel a certain way.

Example:

Bob: Did you see that ad? It’s so sad, I cried. That group says it will help those poor kids. We should send them some money.

So what is the conclusion of this? To construe this as a good argument – “if you feel sorry for poor kids, you should give money to any organization that says it will help them.”

Does that make sense?

Appealing to fear is a way politicians and advertisers and especially propaganda pushers manipulate people.

Examples:

An appeal to fear is bad if it substitutes one legitimate concern for all others, clouding our minds to alternatives.

Bottom line: An appeal to emotion in an argument can be good or can be bad. Being alert to the use of emotion helps to clarify the kinds of premises needed in such an argument, so we can more easily analyze it.

If emotion is the only premise to the argument – be aware!

Cause and Effect Analysis and Critical Thinking

What is a cause?

Consider this statement: “GDP declines in the first quarter due to bad weather.”

Bad weather is seen as the thing that somehow caused GDP to decline. So it is not just that bad weather existed, it is that the fact that it existed caused GDP to decline.

So bad weather is a cause and declining GDP is an effect?

But what exactly is “bad weather?”

But what exactly does “declining GDP” mean?

Whatever cause and effects are we can describe them with claims.

So we need to look into the claim very carefully.

We know that GDP declined (at least that is what those who come up with GDP claim happened) and we know some things about the weather. Given how we define “bad” – we can say that both of those things are true.

But can we say that one caused the other? What is the relationship?

Normal Conditions: For a causal claim, the normal conditions are the obvious and plausible unstated claims that are needed to establish that the relationship between purported cause and purported effect is valid or strong.

GDP was growing up until the time the bad weather hit.

There was no other incident during the time that would cause GDP to decline.

Etc.

The Cause Precedes the Effect

For there to be cause and effect, the claim describing the cause has to become true before the claim describing the effect becomes true.

Would we accept that bad weather caused GDP to decline in the first quarter if the bad weather started at the end of the first quarter?

The Cause Makes the Difference

We often need a correlation to establish cause and effect. But a correlation alone is not enough.

For there to be cause and effect, it must be that if the cause hadn’t occurred, there wouldn’t be the effect.

If bad weather had not happened, GDP would not have declined. That is key.

Overlooking a Common Cause

Bob: Betty is irritable because she can’t sleep properly.

Bill: Maybe it’s because she’s been drinking so much espresso that she’s irritable and can’t sleep properly.

Bill hasn’t shown that Bob’s causal claim is false by raising the possibility of a common cause – one that caused both the irritability and the lack of sleep.

But he does put Bob’s claim in doubt.

We have to check the other conditions for cause and effect to see which causal claim seems most likely.

Tracing the Cause Backwards

Betty is irritable and can’t sleep.

She drinks espresso.

She drinks espresso though because it helps her work out harder.

She has to work out harder in order to win the “fitness queen” competition.

She has to win the “fitness queen” competition in order to win Bob’s heart.

So really – it’s all Bob’s doing that Betty is irritable!!

We stop at the first step in our analysis – typically – because as we trace the cause back further it becomes too hard to fill in the normal conditions. But we do have to be aware that there might be an important cause that came before the cause we are thinking about.

Summarize so Far: Criteria for Cause and Effect

Here are the necessary conditions or criteria for there to be cause and effect, once we describe the cause and effect with claims:

· The cause happened (the claim describing it is true).

· The effect happened (the claim describing it is true).

· The cause precedes the effect.

· The cause makes a difference – if the cause had not happened (been true), the effect would not have happened (been true).

· There is no common cause.

Two Mistakes in Evaluating Cause and Effect

a. Reversing cause and effect

b. Looking too hard for a cause

This can lead to the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy (post hoc for short). We see something happen, then we see something happen afterwards – jump to the conclusion that the first caused the second.

Check Yourself by Thinking About These Responses to a Causal Claim:

· Did you ever think that might just be a coincidence?

· Just because it followed doesn’t mean it was caused by . . . .

· Have you thought about another possible cause, namely . . . .

· Maybe you’ve got the cause and effect reversed.

· Not always, but maybe under some conditions . . . .

Reasoning by Analogy

A comparison becomes reasoning by analogy when it is part of an argument:

On one side of the comparison we draw a conclusion, so on the other side we should conclude the same!

“My love is like a red, red rose” is a comparison - not really an analogy. There is really no argument – what conclusion is being drawn by Robert Burns?

Just that his love is like a red rose in some way.

Analogies are often only suggestions for arguments. But at least there is an argument in there somewhere!

Example: “Blaming soldiers for war is like blaming firemen for fires.”

Analysis: This is a comparison. But it’s meant as an argument as well:

We don’t blame firemen for fires.

Firemen and fires are like soldiers and wars.

Therefore, we should not blame soldiers for war.

Sounds pretty reasonable.

But in what way are firemen and fires like soldiers and wars? They have to be similar enough in some respect for this remark to be more than suggestive.

What are important similarities?

Wear uniforms

Answer to chain of command

Fight

Work done when fire/war is over

Lives at risk in work

Fire/war kills others

Firemen don’t start fires – soldiers don’t start wars

Usually firemen and soldiers drink beer

If you say, “so what” about that last on the list – you are on your way to deciding if the analogy is good or not. It’s not just any similarity that is important.

There must be some crucial, important way that firemen fighting fires is like soldiers fighting wars, some similarity that can account for why we don’t blame firemen for fires that also applies to soldiers and war.

Some similarities don’t matter.

Which do?

You shouldn’t blame someone for helping to end a disaster that could harm others if he didn’t start the disaster.

That’s the argument. That’s the analogy.

Judging Analogies

Just saying that one side of the analogy is like the other is too vague to use as a premise. Unless the analogy is very clearly stated, we have to survey the similarities and guess the important ones in order to find a general principle that applies to both sides. Then we have to survey the differences to see if there isn’t some reason that the general principle might not apply to one side.

Example: It’s wrong for the government to run a huge deficit – just as it’s wrong for any family to overspend on its budget.

Be careful – is this the fallacy of composition? Or are there comparisons that might make a valid argument?

Evaluating an analogy:

· Is this an argument? What is the conclusion?

· What is the comparison?

· What are the similarities?

· Can we state the similarities as premises (for an argument) and find a general principle that covers the two sides?

· Does the general principle really apply to both sides? Do the differences matter?

· Is the argument strong or valid? Is it good?

So - is this a good or bad analogy?

In 2013, 32,850 people died in automobile accidents. Even so, we should not ban automobiles.

Oil spills are accidents too, therefore, we should not ban pipelines or oil drilling rigs.

DO ICE